There has long been a tradition of cross-cultural borrowing, wherein artists (often from a so-called Western culture) assimilate the artistic traditions of other, culturally different sources. Often, the borrowers see the source cultures as more primitive than their own, which leads to an interesting paradox: they believe themselves to be superior to – or more advanced than – the “other” culture, but at the same time they see the other’s art as revolutionary and fascinating simply because it is so different from anything they have experienced before. A well-known example of this phenomenon is the inspiration that Pablo Picasso received from Africa . Picasso was known to admire African art, and several of his figures (such as those in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon) show a distinct resemblance to African masks, but he refused to acknowledge a connection between the two. Famously, Picasso said “I have felt my strongest emotions when suddenly confronted with the sublime beauty of sculptures executed by anonymous artists of Africa ” while, on another occasion, stating “African art? Never heard of it”.

Van Gogh - "Bridge in the Rain"

Hokusai - "Red Fuji"

Japanese artists’ unique conception of the variable perception of color – as opposed to traditional portrayals of color as a constant – spoke strongly to the Impressionists’ desire to portray the transformative qualities of light. Before long, artists across Europe were showing the influences of Japanese art on their styles and compositions. Vincent van Gogh, for instance, created several direct copies of prints from Hiroshige’s One Hundred Views of Edo, applying his unique textural style to the unchanged compositions. He also used ukiyo-e prints as background décor in several portraits. Van Gogh’s appropriation is unusual among other painters in the Japonisme movement in that he used Japanese images directly, whereas others more subtly integrated individual elements of Japanese style into their own artistic vision. Claude Monet is an excellent example of this. In Japanese art, he saw liberation from traditional painting styles and a way for him to portray the world he saw with new, more vibrant eyes. Monet was particularly inspired by Hokusai’s work, including a collection of prints depicting Mt. Fuji Fuji

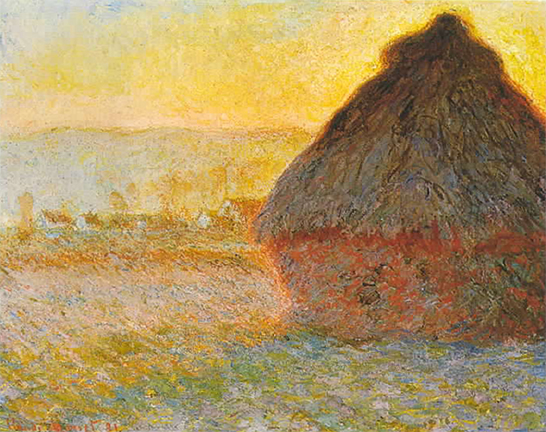

Monet - "Haystack, Sunset"

Monet also showed Japanese influence in his eventual shift towards natural subjects. After 1890, Monet painted only natural scenes, no longer using human figures. A description often placed on Japanese art at the time was “decorative”. This was intended by critics as an insult, implying the art to have no purpose or depth. However, most in the Japonisme movement appreciated the decorative quality. As Monet aged, his paintings became more and more decorative, neither telling any sort of story nor depicting an event; instead, they simply contained mountains or water lilies or snowy landscapes that the viewer could almost step into – scenes that evoke a Buddhist sense of spirituality towards nature. Though there are exceptions, the Japonisme movement was generally respectful towards their inspiration and the Impressionists only took graphic elements that they could apply to their own work. I see this as a positive type of appropriation – or, at least, an innocuous one. The original art was not degraded or devalued, and it was done with a genuine appreciation of the source.

Promotional art for "Avatar: The Last Airbender"

On the other end of the spectrum is Samurai Jack. In it, a swordsman from a vaguely Edo-period village is transported into the future and devotes his life to fighting the demon that has enslaved the world in his absence. This series, created by Cartoon Network, does not draw visual inspiration from anime. The drawing style is heavily stylized and holds a very unique – and visibly Western – aesthetic. However, the actual content of the series is distinctly Japan-inspired. The title character wears traditional samurai garb, ties his hair into a top-knot and carries a katana, all of which are stereotypical Japanese cultural traditions. His enemy, the demon Aku, takes its name from the Japanese word for “evil” and resembles illustrations of oni demons. Is this a more egregious example of cultural appropriation than Avatar? Jack and Aku are the only Japanese characters in the industrial, dystopian future portrayed in Samurai Jack. One could argue that this places the Japanese characters into a position of otherness or foreignness. Indeed, Jack’s sense of alienation in a strange world is a recurring theme in the series. However, this need not be viewed negatively, as Jack is also portrayed as heroic, generous, and committed to his goal. Additionally, the entire series is something of an homage to samurai films, containing stylishly choreographed fights as well as cinematic moments of serenity. The creators clearly have a love for the genre. Though it may toe a thin line with regards to stereotypical Japanese characters, both in appearance and demeanor, I do not find it terribly difficult to label the cartoon as an affectionate tribute as well as an appropriation. Why is it that shows like Avatar and Samurai Jack do not receive the same scrutiny that the Impressionists did when they began adopting Japanese techniques? Some may argue that cartoons are not perceived as fine art, which leads us to forget them as anything but entertainment. However, it may be a product of increased globalization. As countries share more and more of their own cultures with the rest of the world, perhaps the distinctions between our cultures become blurred to the point where we are no longer concerned when an artist from one society is using elements from another.

The "Red Fuji" image doesn't show.

ReplyDelete...Post part IV!

ReplyDeleteThis is really interesting, Patrick. I'm enjoying it. It's definitely a 'delving into' appropriation that's especially relevant in the world of The Internet, where sources often go unnamed and unknown; not to mention, ease-of-access means we can look at images from God-knows-where and take stylistic measures in our own art that we appreciate from others' art. It's definitely a thin, fine, small, really-fucking-hard-to-see line that separates 'copycats' from 'artists,' and one that you know I myself have had difficulty balancing upon.

Thanks for sharing this. :)

For what it's worth, I plan to include my bibliography at the end of all this. :) Though I haven't cited the sources for my images, have I..?

ReplyDeleteGlad you like it!